At some point in your life, if you’re lucky, you might receive a large sum of money. It might be from a maturing savings or investment plan or from the sale of a business or asset such as a house. It might be an inheritance or severance package – or even a lottery win.

However you get this money, it’s at this point that you face a dilemma if your plan is to invest it: do I invest it all at once or do I drip it into the market in installments over time?

Faced with this decision, many investors prefer to spread the investment out. So instead of buying at a single price, the level at which they invest in the market is averaged out.

This kind of investment approach is sometimes known as “pound-cost averaging”. But it can come with a cost.

Packing in protection

The idea behind pound-cost averaging is to provide some protection against the possibility of the market dropping sharply shortly after the money is invested. After all, no one wants to accidentally buy at the top of the market.

So instead of the entire investment suffering this loss, only the invested portion does. The remainder, in theory, is then invested at lower prices. In this way, pound-cost averaging can work well in a falling market.

However, there is a problem: markets tend to go up more often than they go down. This means that with pound-cost averaging you’re more often likely to buy when prices are increasing rather than declining, which would be an inefficient strategy.

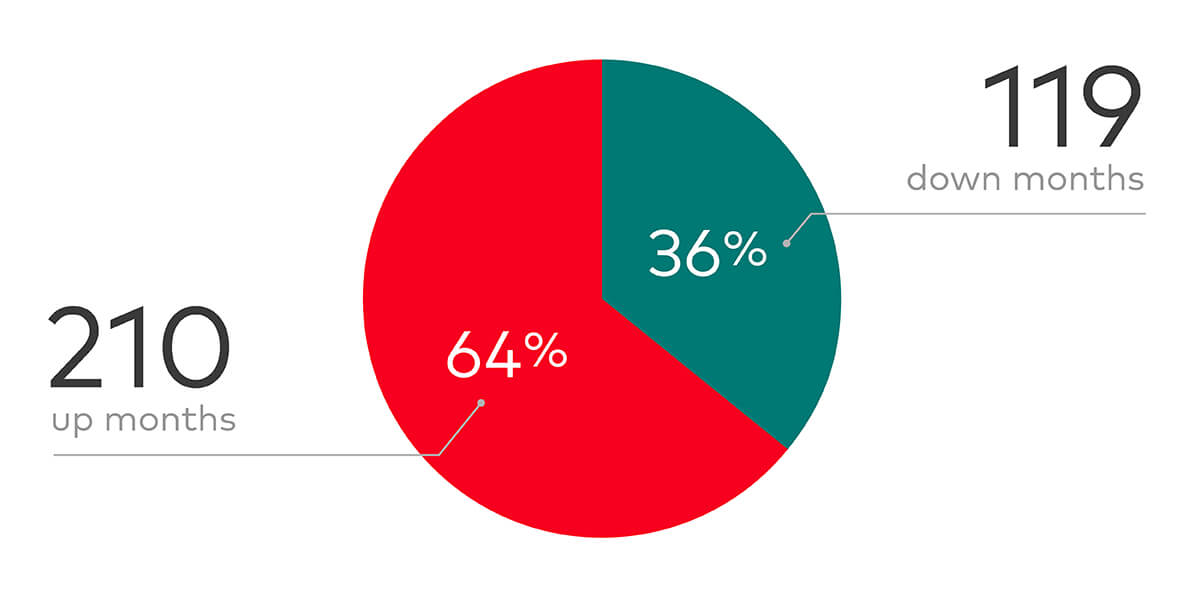

The chart below underlines that. Based on the FTSE All-World Index it shows how global shares have ended higher than the previous month in almost two of every three months since the index was launched at the end of 1993.

Up vs down

Source: Vanguard calculations using data from Morningstar. Stock market represented by the FTSE All-World Index in total return, GBP terms from 31 December 1993 to 31 May 2021. Note: Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Skewed allocation

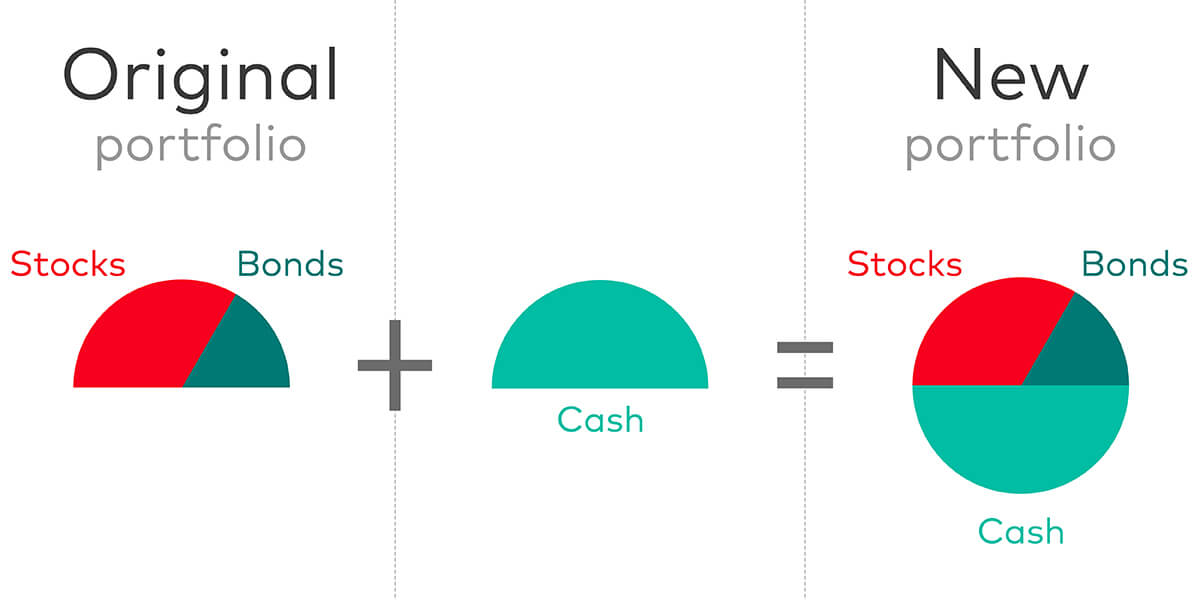

Another drawback to pound-cost averaging is that it will alter the asset allocation of your existing portfolio until the new amount is fully invested. That is, any extra cash you hold could skew your overall mix of investments and make it different to what you’d originally planned.

For example, say you have a portfolio that’s 60% shares and 40% bonds. Now imagine receiving a lump sum that's equal in value to this portfolio. Basic maths dictates that your new portfolio will be split 30% stocks/20% bonds/50% cash. The diagram below illustrates this.

Source: Vanguard calculations

That's a very different allocation and one that is unlikely to align with your goals – something that would not be in keeping with our four tried and tested investment principles. Given research showing the importance of strategic asset allocation to investment outcomes, it would potentially also lessen your chances of investment success1.

What’s more, cash earns a very meagre return and will drag on your portfolio’s overall return. And if the cash never gets fully invested – perhaps because you forget about it or are unnerved by a market decline – this cash drag can persist indefinitely, resulting in permanently lower returns.

Better than nothing

So, is pound-cost averaging without any value whatsoever? In fairness, no. It can be a perfectly valid strategy because it can provide insurance against regret. You might get lucky with your timings too.

Nobody likes the idea of investing a significant sum of money, only to see the market drop immediately afterwards. For some investors, this fear of regret leaves them paralysed. They decide to wait until they feel more confident about the market. But this time may never come.

So, for these investors pound-cost averaging may be a way to overcome their paralysis and at least get some money into the market.

Like all insurance, this hedge against regret comes at a cost. Most of the time, pound-cost averaging will lead to lower long-term returns, meaning investors would have been better off investing their funds all at once. But if you’re fearful of a market downturn, pound-cost averaging might at least provide you with insurance against regret – especially if the alternative is not investing the money at all.

Not to be confused with…

One final point of order: the pound-cost averaging described in this article should not be confused with the regular investments you might make out of your salary with a direct debit into an individual savings account (ISA) or self-invested personal pension (SIPP).

These do also help you get invested at different prices and in that sense help average out the overall price at which you get into the market. But they are each lump-sum investments in their own right because you make them immediately as you get paid.

1 Brinson Hood and Beebower looked at returns for 91 US pension funds from 1974 to 1983 and found that roughly 80% of the variance of returns comes from strategic asset allocation. Since then a great many studies, looking at different periods and types of funds, have come to similar conclusions. For a study based on monthly returns for 743 UK balanced funds from January 1990 through September 2015, which reached a similar conclusion, see the Vanguard research paper: The global case for strategic asset allocation and an examination of home bias (Scott et al., 2016).

Investment risk information:

The value of investments, and the income from them, may fall or rise and investors may get back less than they invested.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Other important information:

This article is designed for use by, and is directed only at, persons resident in the UK.

The information contained in this article is not to be regarded as an offer to buy or sell or the solicitation of any offer to buy or sell securities in any jurisdiction where such an offer or solicitation is against the law, or to anyone to whom it is unlawful to make such an offer or solicitation, or if the person making the offer or solicitation is not qualified to do so. The information in this article does not constitute legal, tax, or investment advice. You must not, therefore, rely on the content of this article when making any investment decisions.

If you have any questions related to your investment decision or the suitability or appropriateness for you of the product[s] described in this article, please contact your financial adviser.

Issued by Vanguard Asset Management, Limited which is authorised and regulated in the UK by the Financial Conduct Authority.

© 2021 Vanguard Asset Management, Limited. All rights reserved.